|

Making a custom mold for a fused and slumped glass plate

Joseph Stoltzfus

March 19, 2007

Commercial molds for slumping glass often are based on

simple geometric forms such as circles or squares. Many glass artists

prefer these, perhaps because simple shapes seem to avoid any competing

esthetically with the glass design.

I wanted to investigate other shapes that would keep a

feeling of simplicity but also be felt as something different from a

customary design. But it was important to limit any new design to one

that could be implemented in a home shop.

It is quite possible to use a found object as the master

object, but since I have a basic woodworking shop I elected to make the

master and the mother mold out of medium density fiberboard (MDF). As a

first project, I decided to make a plate with a flat rim and a slumped

depth of 3/8 in.

My procedure for laying out the desired shape, making a

master object, making the mother mold, and making the slumping mold are

described in this paper. The mold has been used twice, and pictures of

the results will be added when available.

For the slumping mold I chose Best Mix Mold Mix, a

proprietary product sold by Aquila Glass School. I mixed and cast the

material according to the guidelines provided by the vendor.

I bought the Best Mix from Aquila Glass School. Their

current address is

Aquila Glass School

1628 N Columbia Blvd

Unit A

Portland, OR 97217

503-240-9449

www.aquilaglassschool.com

Look on the website (either one) for extensive

information about using the Best Mix Mold Mix. They have lots of

experience, and they have expanded their website since I began this

project.

|

After choosing

an approximate design for the mold and plate, I laid out the

curved sides on paper, drawing the lines along a flexible metal

ruler pushed against clamped stops on a drawing board.

The same method

was then used to draw the same curve on a piece of 1/8-in MDF. |

|

|

|

The MDF was cut

near the line using a band saw (a coping saw could be used

instead) and then shaped with a block plane and sandpaper to

make my standard curved rule.

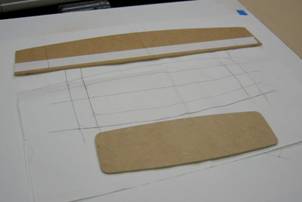

The photos the

full-size drawing of the plate, along with the full size

template of the top of the slumping depression for the mold. The

template was laid out by using the full-size drawing and the

curved rule, and the corners were marked along the edge of a

penny. |

|

|

The 1/8-in MDF template was shaped by sawing and sanding,

by the same method used for the curved rule. Because the material is so

soft, in a future project ¼-in MDF would be preferred.

To make the master, a 3/8-in stack of MDF was laminated

from layers of MDF. The template was then used to mark the stack,

indicating the top of the slumping depression in the finished mold. The

stack was cut just outside the line on the band saw.

The template was then attached to the top of the stack

using double-sided carpet tape.

Although I used a router to shape the MDF master, it

could be accomplished with hand tools.

|

This is the

router table used to cut the master. The router bit is a 45-deg

bevel cutter with a guide bearing. The template was on top of

the laminated stack of MDF, which is not shown. The router bit

was adjusted to let the guide bearing run on the template as the

cutter made a beveled edge on the master.

|

|

|

|

This is the

mother mold ready for filling with the Best Mix Mold Mix. The

mold is placed on a level tabletop; I used a table saw. A

covered the table with wax paper to control the mess; the mix

sticks to everything just like concrete. The master is seen

glued in the center of the bottom board (made of ¼-in MDF), and

the sides are confined with ¾-in wood dams to make a casting

box. The dams are cut at a 5-deg angle to ensure that the

completed slumping mold can be withdrawn. The dams are attached

with woodscrews. |

|

|

It is necessary to seal the surfaces of the mold box to

prevent water from soaking into the MDF, which would damage the box and

remove water from the mix before it had time to solidify. The varnish

also serves as a release agent, so the mold does not stick to the box

when it solidifies.

I sanded the inside of the box with 220 grit abrasive

paper, wiped out all the dust, then applied four coats of marine varnish

from the hardware store (Ace). I let each coat dry for about 24 hours,

and sanded again after each coat except the last. I was especially

careful to seal the crack where the master was glued to the bottom of

the mold box. Note that the bottom of the mold box meets the surface

that becomes the top of the slumping mold.

To avoid having water from the mix run under the dams, I

sealed the boundary between dam and bottom board with a strip of

modeling clay along two sides, and soaked extra varnish into the gap on

the other sides. Neither proved to be necessary.

I estimated the required amount of mix by calculating the

volume of the box. I could do this because the box is very regular, and

I ignored the volume of the master to ensure I would have a little extra

material. For an irregular shaped mold I would have filled it with dry

rice and then measured the rice in a box or with a cup measure. My

estimate for density of the powder was 19 cu-in/lb.

Shortly before preparing the mold mix, I applied a second

release agent (PAM No-Stick Cooking Spray with Olive Oil).

|

The mix was

prepared by combining measured quantities. I weighed out 72 oz.

of the Best Mix powder into a 5-qt. plastic bucket like the one

in the background. The mix comes from the supplier in a plastic

bag inside the box. I weighed 16 oz. of lukewarm water into the

smaller bucket. The scales was a spring balance I bought at a

flea market. |

|

|

The ratio of powder to water followed the vendor’s

recommendation, which was described as” not absolute”. I mixed the

materials into a slurry in the larger bucket, adding water to the powder

a few ounces at a time while stirring with a stick. I stopped adding

water when the slurry seemed almost liquid; I could pick up a bit on the

flat stirring stick, but I was afraid to add more water. It was about

what I remember from watching workers pour concrete. Since I had 3 oz.

of water remaining, I had a ratio of 4.9 parts mix to one part water by

weight.

I stirred the mixture for five minutes, enough for

thorough wetting but still allowing time to pour the mold before the mix

began to set. Do not shorten the five minutes, because complete wetting

of every particle is essential.

|

The box was

placed on the table and leveled using wooden wedges. The mixture

was poured into the mold box and leveled with the scrap of

lumber (the screed) behind the box.

The 4.5 lb of

powder with 13 oz. of water proved to be just enough. I allowed

5% extra; I should have allowed 15% extra.

When the box was

filled, I covered it with plastic wrap and left it to set for 24

hours. |

|

|

I intended to place nails in the corners to maintain vent

holes, to prevent air being trapped and blowing bubbles when the mold is

used. But when the mix was first poured, it was too soft to support the

nails upright and when I returned 3 hours later the mix had set.

|

This shows the

box after the mold was removed from the casting box. Although a

5-deg draft was allowed in the dams, I needed to remove two

sides that were stuck to the mold because of the modeling clay.

One of the dams was stuck to the base, probably because of the

varnish run under the dam, and it had to be pried off.

There was no

damage to the mold.

The dam can

easily be replaced if the box is used again. |

|

|

|

The mold is

shown after it was removed from the casting box. The surface was

very smooth, except for two very small divots in the upper flat

surface. These will be filled with modeling clay when the box ix

used for slumping.

It was clear

that air would be trapped in the corners when slumping, so it

was necessary to drill vent holes in the completed mold. |

|

|

In future I will devise supports to position the nails

immediately upon pouring and support them until the mix has set.

|

These tools were

used to drill vent holes.

The tools

included a 3/32-in. masonry bit, a 5/64-in. diamond burr made

for a Dremel tool, a set of 20 inexpensive diamond drill bits

from Harbor Freight, and a sharp pointed awl.

Instead of a

Dremel tool, I used an ordinary cordless drill run at low speed.

|

|

|

|

Holes were

drilled from the back and from the front. This picture shows

holes drilled using the 3/32-in. masonry bit.

I was careful

not to drill so far as to break into the bottom of the mold. The

drill worked best at low speed, and it was slow enough to permit

checking the depth frequently. The mold mix is quite

homogeneous, and could be drilled slowly. |

|

|

|

The holes were

then drilled with the diamond bits from both inside and outside

until they almost met. Forcing through with the awl then

completed them.

This was a

delicate and nerve-wracking procedure, but you can see that the

resulting vents appear centered in the bottom corners of the

slumping depression and have not chipped out significant divots. |

|

|

Before use for slumping, it is necessary to cure the mold

at high temperature to remove all traces of moisture. It is best first

to let the mold dry in air for a reasonable time. I let it dry in a

living space at 70 deg F and 50% relative humidity for about three days.

Then the mold was cured on the following schedule:

Mold Cure Schedule

|

Ramp (deg F/h) |

40 |

55 |

75 |

9999 |

|

To (deg F) |

225 |

400 |

1400 |

Room |

|

Hold (hr) |

2.00 |

1.00 |

0 |

0 |

|

This is a fused

two-layer item ready to be placed on the mold for slumping. The

base layer is 3-mm clear and the top layer is 3-mm color. The

top layer was cut about 2 mm smaller all around than the base.

The curves were cut using a curved template. The base was cut

first and used to draw the shape on a sheet of drawing paper,

and then cutting guide marks were placed on the paper to aid in

positioning the colored piece and template.

|

|

|

Above are bottom and top views of the two-layer item

after slumping. The bottom surface, which was in contact with the mold,

has an excellent smooth finish. The inside is fire polished as expected.

In future I would use a slightly longer slump time to make the outside

bottom flat.

Results:

The fully cured mold appeared to be in good condition and

was free of cracks. Surface was smooth throughout except for two small

divots described above. These were filled with modeling clay when used

for slumping for the first test, but were ignored for the second test.

There were numerous hairline surface cracks, but these did not affect

the integrity of the mold and were anticipated based on information from

the vendor.

The first piece slumped was a single layer of iridized

black glass slumped iridized side up. The firing schedule for this item

was made fairly short because of the single layer. The mold showed no

damage whatever in use. A second piece was fused and slumped, as shown

in the photos above. No kiln wash was applied for either piece, and was

not needed.

Conclusion:

This project demonstrated the use of Best Mix as a

reliable material for making custom slumping molds. It can be used in a

home shop with simple materials and tools. I will use it for further

exploration of custom forms.

|